本文来自OLI建筑设计事务所创始合伙人、木心美术馆主创建筑师Hiroshi Okamoto(冈本博),关于汪曾祺纪念馆与其作品相似度的争议,也关于木心美术馆背后的故事。

This is an essay provided by Hiroshi Okamoto, the founding partner of OLI Architecture and the lead architect of Muxin Art Museum. It is about the controversy about the similarity between Wang Zengqi Memorial Hall and his works, and the story behind Muxin Art Museum.

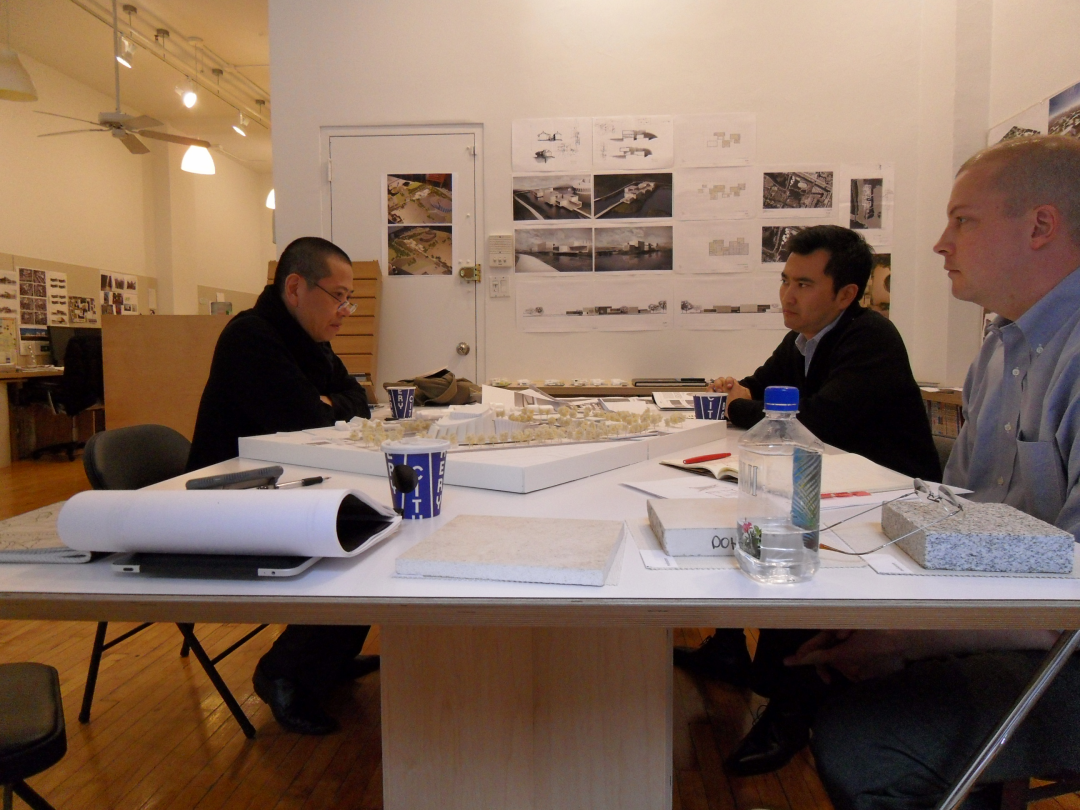

当汹涌舆论稍散,冈本博希望呈现更全面、客观的思考。尤其打动我们的,是文中一张设计会议照片里,木心的侧影。

When the turbulent public opinion dissipated, Okamoto hopes to present his thinking in a more comprehensive and objective way. What moved us in particular was the silhouette of Mu Xin in a photo of a design meeting in the article.

有方欢迎更多围绕行业热点的一手回应与客观讨论。期待你的来稿。

Youfang welcomes more first-hand responses and objective discussions around industry hot spots. Looking forward to your contributions.

作者 冈本博Hiroshi Okamoto,AIA, LEED A.P.

译者 王孟瑜 黄恺 / 有方

一位英国籍牧师、作家和艺术品收藏家,查尔斯·卡勒布·科尔顿,曾于1824年说过这样一句话:“模仿是最诚挚的恭维。”后来,爱尔兰籍作家、诗人奥斯卡·王尔德在原有基础上将其扩展成:“模仿是平庸者对伟人最诚挚的恭维。”这句话也随之闻名于世。

It is perhaps fitting that this quote, which is attributed to the English cleric, writer, and art collector Charles Caleb Colton from 1824, was made famous by the Irish writer and poet Oscar Wilde, a literary giant that MuXin admired.

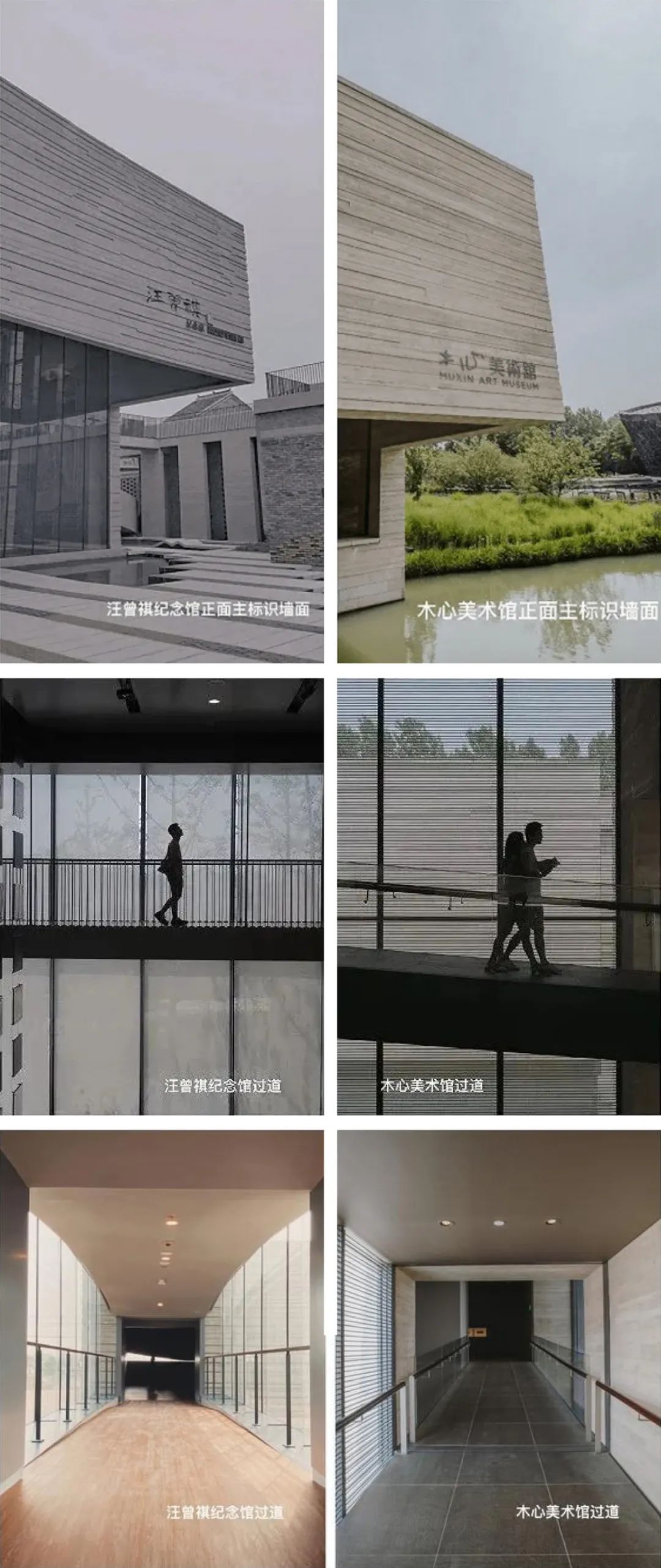

当我的合伙人林兵告诉我,新建成的汪曾祺纪念馆与我们的木心美术馆有些雷同,那时我立刻想到了科尔顿这句话。事实上,我本人没有亲自到访过汪曾祺纪念馆,对于设计方的设计意图也没有任何负面的揣度,只是听闻汪曾祺先生是一位伟大的作家,我为此感到了一丝沮丧和遗憾。

When I heard from my partner Lin Bing how the new Wang Zeng Qi Museum had some similarities to our design of the MuXin Art Museum, I immediately thought about Colton's quote. I admit I have not visited the museum in person and had not thought anything negative of the designers' intent, only a slight disappointment for Wang Zeng Qi whom I heard was a revered writer of his time.

会产生如此反应,是源于我看到了两个美术馆的对比照片,我很好奇设计者为何会将木心美术馆作为他们设计灵感的重要来源。于是我不禁开始想象,假如我们有幸成为那个项目的建筑师,我们将怎样通过调研尝试各种想法,将怎样尽己所能去详尽地了解设计的主人公——汪曾祺先生。这个探索的过程发生在我们的每个项目中,无论项目大小。在不断尝试概念上的一切可能性时,我们时刻警惕错过任何一个微小的灵感,因为这可能会使我们失去一个完善概念和设计的机会。

My reaction came from looking at the comparison images between our museums and wondering how the designers came to make the MuXin Art Museum an important source for their design. I then began to imagine how, if we had been honored to be the architects for his project, our process would have been testing various ideas and methodologies through inquiry, in an exhaustive process to learn more about the subject matter, Wang Zeng Qi. This process is typical for all our projects, whether big or small, while we test and explore conceptual possibilities and inspiration always on guard to avoid missing an opportunity that would make the architectural concept and design better.

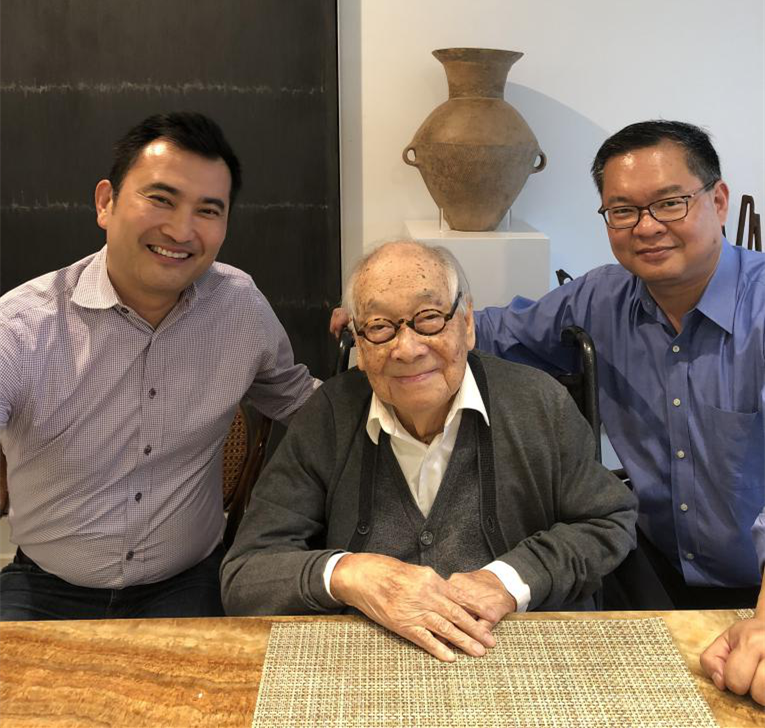

诚然,木心美术馆这个项目有些许不同,因为我们有机会与木心先生进行了面对面的交流。2011年年中,我的合伙人林兵与木心先生有过一次会面,随后的秋天我们又一同造访了他的家,那时陪伴他的还有他的学生及挚友陈丹青先生。同年年底,木心先生逝世。那次会面对我们影响深远,也让我们与陈丹青先生结下了深厚的友谊。在随后四年半的项目推进中,他为我们提供了许多指导和帮助。

Admittedly, in our case for the MuXin Art Museum, it was a little different as we were able to meet with MuXin personally, first my partner in mid-2011 and then together in the fall at his home with Chen Dang Qinq, his disciple and faithful champion, before his passing in December of 2011. We were profoundly influenced by this meeting and our subsequent friendship and guidance from Dan Qing during the evolution of the four-and-a-half-year project.

细细揣摩科尔顿这句话,其实,如果有人对某些事物或行为进行了模仿,这意味着他怀有欣赏的态度,以至于想要重复它。回想当我得知汪曾祺纪念馆争议时的感受,最初其实不是沮丧,而是一种更本能的反应——我感到了小小的骄傲和满足。这意味着我和我的同事、业主、投资方以及几年的努力和艰辛,得到了他人的认可。

In unpacking Colton's quote, if one imitates something or an act, it means one admires that thing or act enough to replicate it. Looking back at my reaction to the news of the Wang Zong Xi museum, disappointment was not, in fact, my very first reaction: I actually felt a small reflexive feeling of pride and gratification knowing that the product of years of hard work with colleagues, clients, stakeholders, and all of the collaborators was also being recognized as a model to be imitated.

人类自婴儿时期便习惯于通过模仿来学习语言和社交技能,通过模仿来学习的方式潜藏在群体动机与压力中。在不同社会和文化里,“从众”都作为一种有效的机制,帮助人们学习并维护自身的文化准则、行为和态度[1]。作为一个在传统日本家庭中长大、在美国工作的人,文化之间的碰撞时有发生,我时常要面对社会从众心理带来的利弊,以及其中复杂而微妙的差异。事实上,在大多数文化中,群体都会带给人们巨大的压力和动机去选择从众。这能带来一种心理上的安全感,是一种本能的、根深蒂固的生存机制。但是,真正将人类和动物区分开来的——至少是被理论广泛认可的——不是其生存能力,而是人类独一无二的思考、自省以及想象的能力。我们树立起时间的架构,超强的记忆能力使我们得以进行投射、抽象,于是这个构筑的世界便成为了创造力的发源地。创造力又使艺术和设计成为可能,使其得有意义,同时推动着社会与文化的前行。

It is undeniable that we as humans learn from each other as we are conditioned even from infancy to learn language and social skills through imitation, a behavior that is well researched. “Imitative learning resides in the social motivations and pressures which influence human copying behavior. In various societies and cultures, conformity is a powerful mechanism through which “cultural norms, behaviors, and attitudes are learned and maintained.” 1 Growing up in a traditional Japanese family, I was often confronted with the complex nuances of the pros and cons of social conformity living in dual, and often times, clashing cultures such as the United States and Japan. In fact, in most cultures, be it the US, Japan or many others, the motivation and pressure to conform is so great that we conform to beliefs even when we do not necessarily share those beliefs, seeking harbor in the safety of numbers or the security of being “average.” It is an instinctual ingrained survival mechanism, which may not be so different from the advanced mimicry many species exhibit to attract mates or to avoid predators. But what separates, humans from animals -- at least what has been widely theorized -- is that we have the unique ability to think, reflect, and imagine and not just to survive. We created time as a construct and our enormous capacity for memory affords projection and abstraction allowing for places where creativity can happen. Creativity which in turn makes art and design possible and meaningful and pushes societies and culture forward.

导师贝聿铭曾给予我和我的合伙人极大的鼓舞,我们也一直深受他的影响。但回想二十年前我与他的第一次会面,那时我心中便明白,我不是要去模仿他的建筑,而是去学习他的本领、技巧、抱负、长处以及知识。正是这些要素使他成功把握住机会,最终留下无数佳作。我的目标并不是去模仿那些程式化的内容,而是让知识成为我未来发展的坚实基础。在此之上,我才可以探索更新的理念,寻求更好的机遇,为艺术与社会的发展创造更多可能。

As my partner and I were greatly inspired and influenced by our mentor I.M. Pei, I knew before the first time I met him over twenty years ago that it was not the buildings I wanted to imitate but the skill, guile, ambition, strength, knowledge, and will it took him to create opportunities to shape some of the most prestigious institutions in the world. My goal was not to simulate the same rigid hardware, but to build upon the knowledge that I was to gain through years of tutelage to be able to position myself to push new ideas and possibilities, and to create new opportunities and outcomes for the betterment of the arts and society.

我并不是想表达作家、艺术家或建筑师之间从不相互模仿,他们只是将其视为一种向他人学习的方式,尤其是向那些激励影响过他们的人。在亚洲文化中,尤其在以师徒制为背景的传统艺术环境下,模仿一直被视为一种尊重的象征。但我更认可这是一个世界性的普遍现象,就像二十世纪杰出的西方艺术家,巴勃罗·毕加索曾经说过:“优秀的艺术家复制,伟大的艺术家窃取。”换句话说,优秀的艺术家仅仅是模仿他人的作品,而伟大的艺术家则有选择性地从不同来源提取元素,运用其丰富的想象将不同元素带来的灵感结合起来,创造一个属于自己的独一无二的作品。这个过程需要分析能力,需要批判性思维,需要整合与反复打磨——换言之,需要创造力。

This is not to say that writers never imitate other writers, or artists or architects never imitate each other for that matter. They do as a way of learning, especially from those that move and influence them. In Asian cultures, there is a long established history of the traditional arts where imitation is often seen as a symbol of respect, especially in the context of master/apprentice relationships, yet I would posit that this is more an universal phenomenon that can be traced and correlated to long periods of established socio-economic value systems in pre-modern times. Pablo Picasso, one of the great western artists of the 20th Century is often (though it is open to debate), quoted as saying: “good artists copy, great artists steal.” In other words, a good artist simply copies another person’s art, but a great artist selectively takes (steals) elements from multiple sources and then imaginatively combines their influences to invent something that is uniquely their own through a process that takes analysis, critical thinking, synthesis, and iterative refinement -- or in other words: creativity.

随着科技的飞速发展,以及信息处理、可视化和建造工具的不断进步,我们有了更多机会去实践创想,使新的建造方式和有意义的空间体验成为可能。我不是历史学家,但确实认为我们在经历单一风格与主张的快速更迭——现代主义、后现代主义、解构主义、新现代主义等。某种意义上,我们正处于后-后现代主义时期,被大量的数据和信息所淹没。不同风格能够跨越地域和历史文脉实现共存,而这无关于构成它们的价值观念。近年来,航空旅行逐渐普及,AI算法日益强大,社交媒体即时访问图像及评论的功能重塑了传统意义上时间和空间的因果关系。这些技术的进步,使图像表达与现实空间之间的历史叙事纽带,被重新审视。

With the explosion of technology and the ever-growing availability of sophisticated information, visualization, and fabrication tools in the architect’s toolbox, there are so many possibilities to exercise our creative energy and to bring new constructions and meaningful experiences to fruition. I am not a historian, but we are rapidly passing singular styles, trends, movements, Modernism, Post-Modernism, Deconstructivism, Neo-Modernism, and so-on and so-on. In some sense, we are in a Post-Post-Modern era and inundated with data and information where multiple styles can co-exist regardless of regional or historical context and devoid of their formative associative values. As air travel becomes ubiquitous, AI algorithms become more powerful, and instant access to imagery and commentary through social media recombine the typical causal relationships and associations to place and time, technology has allowed us to quickly unravel the historical narrative ties between representation to place and image to reality.

这种高速发展的趋势是强有力且振奋人心的。但与此同时,在我职业生涯的成型期,我也亲身经历了其令人沮丧的一面:数量激增的当代建筑也有些日趋一致。中国在过去的25年间经历了空前的建设热潮,为成千上万人带来了变革性的建筑体验,这便是这一现象的加速版典型。中国丰富的历史文脉为其发展提供了肥沃的土壤,新建筑的形态也各有千秋,既囊括了平庸、古怪、随处可见的西式杂糅,也有深受扎哈影响的流线形态、错综复杂的本土混搭,以及介于它们之间的其他风格。但毫无疑问的是,如今的中国正在进行非常有意思的建筑探索。正如我的妻子曾对我讲:“世界并没有变得越来越小,反而是人们自己的世界变得越来越大。”历史上那个少数人为多数人“制定意见”的时代已经过去了。可以理解的是,模仿相较于对意义和价值的探索,是一种更简单的选择;而尽管我们的时代为创新留出了丰富的可能,这依然是一种更高的要求。

This accelerating trend is powerful and exhilarating, and yet also debilitating as I have experienced first-hand in the formative years of my career development, how contemporary architecture has proliferated throughout the world and become ever more inspiring, yet at the same time, ubiquitous. China, which has seen an unprecedented twenty-five year construction boom bringing new transformative architectural experiences to hundreds of millions of people is in my opinion, the accelerated archetype of this phenomenon. Perhaps it is the historical or a-historical context that provided the fertile grounds, but the new architecture of the past decade ranges from the mediocre, anodyne, corporate “western” architecture of everywhere (or now nowhere), to Zaha influenced fluid morphological urban interventions to intriguing vernacular mashups, and every flavor in between. Today, there is no doubt in my mind that some of the most interesting architectural experiments are happening in China . As my wife once told me, “The world is not getting smaller, people’s worlds are getting bigger,” and it is no longer the historical “few” insiders and experts that curate opinion for the masses or the “average citizen.” In this sense, it is understandable but ironic that mimicry becomes an easy alternative to co-opting meaning and value as the plethora of possibilities of making something new or meaningful may seem daunting and paralyzing for those tasked to produce but challenged by imagination.

当过去严谨的批判标准已式微,人们通过滑动屏幕就可以轻松获取建筑图像和空间表达,这使大家越来越轻易相信,自己仅仅通过看图,就能将建筑的图像客观化,进而看透建筑的本质。当然,人类天生是视觉性动物,几乎有80%的信息是通过图像输入大脑的。但当我们仅靠看图去“消化”一个建筑时,建筑又是什么呢?我和身边的每个人一样,都享受图像带来的快乐;但在现实的体验中,你可能时而失望透顶,时而欣喜若狂,那些戏剧性的体验也许会改变你的生活,甚至带来对世界的全新认知。能带来这种变革性体验的,往往才是最精彩的建筑;而这个难以企及的目标,也是我们工作室一贯的追求。

As traditional critical rigor has waned, and architectural imagery and spatial representations have become accessible to the masses from a swipe of a screen, an exacerbating problem that happens too often is that one believes that acquiring the image, or viewing it, automatically allows the individual to quantify what the architecture is, objectifying the consumed image, and by default, architecture. Humans by nature are visual animals, processing up to 80% percent of input and impression through imagery, but what is architecture if we just consume it in images? I enjoy images as much as the next person, but the reality when you experience things in person can range from the typical disappointment to the occasional positive, life changing, transformative experience that reveals a new understanding of the world. It is these transformative experiences that we enjoy which are usually the best kinds of architecture. An elusive goal but one that guides our office’s aspirations.

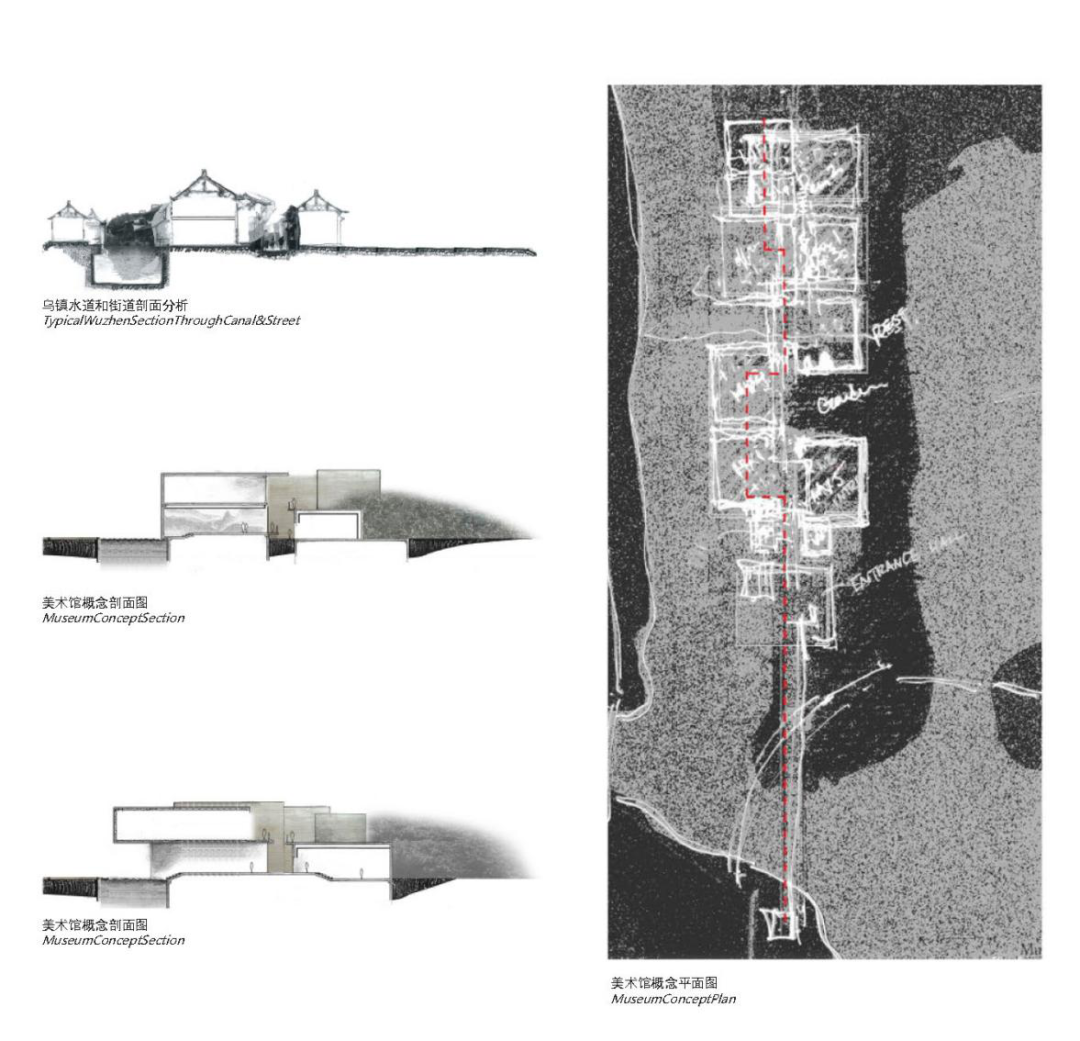

在开始木心美术馆的设计时,首先要了解的是基地的文脉。我们曾多次拜访木心先生的故乡乌镇,去看那里的运河、街道、市场、庭院、桥、阳台,以及一直作为乌镇重要生命线的古老河道。从最开始,我们便设想着做一个能提供有趣体验的景观建筑,它应该与周边喧闹的运河小镇有相似的规模。河道既连接空间,也分割空间,漫步其中的人们将获得不同的亲切空间体验。

When we set out to design the MuXin Art Museum, we wanted to understand the context of our chosen building site. We visited MuXin’s hometown of Wuzhen several times to see the restored landscape of canals, streets, markets, courtyards, bridges, verandas, and the centuries old riverway that was once a vital lifeline for the village. We imagined from the start that the museum itself had to be a landscape of intersecting experiences, similar in scale to the bustle of the popular canal town allowing visitors to construct various intimate experiences where the water was a connector as well as a divider.

接着,我们尝试用一座桥分隔两岸,形成不同的时间感,一边是熙熙攘攘的旅游小镇,另一边则是木心先生的个人世界。这个世界由散落的体块构成,承载着他一生的方方面面,从早期作品,到他的音乐、文学、绘画以及写作。“桥”也是对木心的一个隐喻,它提示着木心毕生融汇东西,在哲学、艺术、文学等领域取得的成就。换而言之,这是一座沟通不同文化的桥,但整体仍是在中国的语境中。

We then set out to change the notion of time via the bridge which separated the visitor from the restored tourist town of Wuzhen to the world of MuXin where discrete volumes were to house various aspects of his life, from his early works and influences, to his music, literature, paintings, and writings. The “bridge” was also a metaphor of MuXin himself, a complex figure who was equally comfortable discussing great Eastern and Western philosophy, art, and literature. In other words, a bridge between cultures, yet still uniquely Chinese.

我们进行了连续的实地考察,随着建筑体量的逐渐缩小,尺度的重要性愈发明晰。于是这个三层建筑60%的空间都被放在了水面以下——包括机械、电气、管道、临时展厅、咖啡厅以及多功能厅。这使美术馆得以契合运河小镇的尺度感。体块之间又设置了垂直和水平方向的一系列连接,为观众提供了不同的游览路线。人们可以依照自己的节奏漫步于展馆之间,去游览木心一生的不同篇章,编织自己理解中木心的人生故事。

Upon successive site visits, the importance of scale became increasing evident as we scaled the project down and put all of the back of house and MEP areas, the temporary gallery, café, and the multifunction space below grade, essentially building a three story museum with 60% of the mass below the waterline. This allowed the building to be built to the scale of the canal town as a series of vertically and horizontally connected volumes affording the visitors various paths to weave their own story of MuXin, like chapters in his life, and to control the speed of time through experiential space.

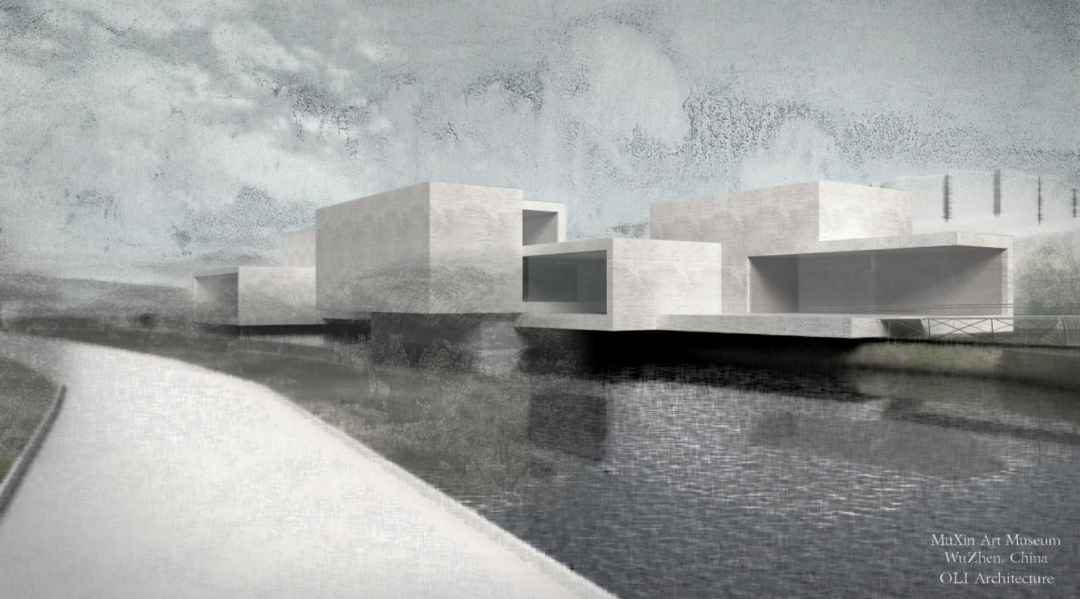

在考虑项目材料时,我们不想直接选择复原乌镇时所使用的材料,这不符合我们对木心先生的理解,况且我们也不能做一个仿制品的仿制品。乌镇本身是一个以砖石建筑为主的小镇,主要使用了水、岩石、灰泥涂料、编条以及木制壁板等材料。但我们的基地位于乌镇的新规划区,旁边是正在建设的乌镇大剧院,周边还有许多规划中的文化项目。2011年秋季,我们向木心先生、陈丹青先生以及陈向宏先生(乌镇旅游股份有限公司总裁)展示了最初的设计草稿和渲染图。这个设计融入了木心先生画作中的山水意象,将其抽象化表达在相互穿插的体块中,并沿着一条中心轴线(或“街道”)布置。令我们欣慰的是,这个想法受到了广泛好评。

When considering the materiality of the project, we knew that we did not want to copy the same material used in the restoration of the canal town. That was not true to our understanding of MuXin and we could not bring ourselves to make a facsimile of a facsimile. The town is essentially a restored masonry town of water, rock, plastered daub and wattle and timber siding, but our given site was a new extension of the town where Kris Yao’s Wuzhen Grand Theater was under construction and other planned cultural projects were under consideration. Our first concept sketches and renders which we showed MuXin, Chen Xiang Hong (Chairman of the Wuzhen Tourism Company), and Chen Dan Qing in the fall of 2011 used actual MuXin landscapes on abstract intersecting volumes placed along a central spine or “street.” To our relief, it was well received.

在材料方面,我们想在混凝土表面做出木板的纹路肌理,为此我们用参数化工具对木板长度进行了像素研究。这种纹路与肌理的质感,宛如木心先生的山水笔墨抽象于建筑表面。在贝聿铭先生手下工作时,露石混凝土一直是大家常用的材料,因此我们对探索其不同表现形式十分得心应手。这种材料是结构性的,同时具有极强的延展性和极高的可靠度。

We then started to play with an idea of printing some of his landscapes as inspiration for textures on the volumes and using board form Architectural Concrete, studying even board length pixilation of MuXin’s landscapes using parametric tools. With our mentor, I.M. Pei, architectural exposed concrete is a material that we used quite often, and we were comfortable exploring various new ways of expression with it. It is structural, yet a highly malleable and extremely honest material.

随着项目由概念阶段不断深化,我们着手将整个建筑放置在900mm的三维模块里。然后我们继续进行分割,将得到的300mm子模块整齐排布于空间之中。接着,这些模块被继续切割,形成了60mm、90mm、150mm三种规格的拉丝木板状模块,表面均覆满线型压痕。这样一来,立面上的每条线都在建筑中无限延伸,像是在空间中被切割出来。为了抽象出木心先生画作中的山水线条,我们建立了一套规则来调节每块板的深度,形成凹凸的表面效果。随着高度升高,我们又建立了另一套规则来打破之前的图案规律,从而产生了微妙的抬升和浮动的外观。选择露石混凝土作为材料,无疑是非常冒险的决定,对于以木材饰面为主的乌镇建筑来说,这甚至是一种略带挑衅的颠覆行为。但在我们看来,这非常“木心”。

As the project progressed through concept to design development, we placed the entire building on a three-dimensional module of 900mm. Sub-modules were created into 300mm where all components aligned in space, and then again divided into staggered and alternating 60, 90, 150mm wire brushed wood (Yellow Pine) board form modules so that every line on our elevation continues through the buildings as if a cut line in space. From there, to abstract the lines of MuXin’s landscape, we created rules to vary the depths of each board line in and out of the plan module and then created another rule to break the pattern as it went higher, giving a subtle lift and floating appearance. It didn’t escape us that our design and use of architectural exposed concrete was a bit risky for the context but subtlety and defiantly subversive that the wood or “木,” which was prevalent in the town as a finish on top of masonry, was used in reverse to cast a masonry structure. It was in our opinion, very MuXin.

那时,我们还是一家非常年轻的事务所,并没有什么东西可以失去,所以我们无所畏惧地为整个项目提供了全部设计。事务所的设计收费不高,因此很多事情需要尽量自己完成。我们聘请一些朋友来帮忙,偶尔也会邀请贝聿铭事务所的前顾问为我们提供无偿咨询,以核查项目的进度。我们最终的工作范围不仅涵盖了建筑设计、工程文件、施工管理,还包括照明设计、标识设计、室内设计、展览和展示设计、零售设计,以及喷泉和景观设计。完成这一切,也许源于“初生牛犊不怕虎”的魄力;但时至今日,我们依然努力在每个项目中都保持类似的设计参与度——对细节的精雕细琢,始终是OLI追求的目标。

We were still a very young company at the time and perhaps we had nothing to lose. Unafraid, we were driven to do the entire design in totality. Our fees were quite low, so we needed to do as much as possible ourselves, and although we hired friends to help or had the occasional pro-bono consultant meeting from gracious former I.M. Pei consultants to check on our progress, our scope entailed not only architecture to construction documentation and construction administration but also, lighting, graphics/wayfinding, interior design, exhibition, and showcase design, retail design, fountain, and landscape design. It could have been our youth and drive, but to this day, it is a scope we still try to negotiate in all of our projects, a project that allows as much as possible a crafted design that encompasses a totality.

贝聿铭先生曾经告诉我们,一个优秀的项目需要具备三个要素:优秀的场地、优秀的项目规划,以及优秀的甲方。回顾这一路走来,木心美术馆被OLI视为我们自己的一个佳作,因为以上三个要素汇集在了一起,并且我们有幸用四年半的时间,实现了最初的设计愿景。我们没有麻木地对待机遇,机遇解放了我们。在木心先生逝世前的一次会议上,他给我们的最后一句话是:“不要害怕犯错。”在整个项目过程中,这强有力的话语一直回荡在我们心中。

As Mr. Pei always used to tell us, to make a great project, you need three things: a great site, a great program, and a great client. In retrospect, we view the MuXin Art Museum as a great project for OLI as those three important elements came together and we were fortunate enough in those four and a half years to be able to bring our design vision to fruition. We were not paralyzed by the opportunity but liberated by it. The last words MuXin said to us in our meeting with him before he passed away was, “let’s not be afraid to make mistakes.” These were powerful words that resonated with us throughout the journey, something that I wish I could have shared with Wang Zong Xi Museum’s designers.

参考文献 References

[1] Over, Harriet and Melinda Carpenter. “Imitative Learning in Humans and Animals.” Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Edited by Norbert Seel, Springer, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_270

译文及编排版权归有方所有,图片由作者提供、版权归原作者所有。欢迎转发,禁止以有方编辑版本转载。

上一篇:业主也能获建筑奖?看看全球9位被评为“年度最佳”的业主

下一篇:经典再读73 | 卡雷别墅:阿尔托式优雅